Introduction and literature review:

Here follows a meta-synthesis of four published papers on online gaming addiction. The purpose of the research is to investigate the costs of online gaming addiction by examining the subjective experience of vulnerable groups engaged, alongside enquiring if there are any benefits for these groups or the application of online gaming in the future. Four main overarching themes emerged from the research focusing on the educational application of gaming most specifically for young people balanced against the current evidence that gaming in its most popular state appears to have a multitude of side effects including the addictive nature of gaming and significant need for regulation.

A literature review for the meta-synthesis was completed to reveal further thoughts about the area of online gaming addiction and to discover what other research has been completed in this area. The review consisted of an analysis of research papers from the University of Wolverhampton library Access BrowZine, PubMed and JSTOR. Using search terms such as ‘online gaming addiction’, ‘gaming addiction’ and ‘online gaming’.

The review mainly uncovered a focus on the negative impact of online gaming for people, most specifically young people (Cisamolo at al, 2020; Yilmaz & Griffiths, 2018; Beranuy et al, 2013). Chen et al (2021) outline the significant neuro-cognitive changes and potential deficits that exist for people with gaming addictions. Alongside this, there seems to be a surge of interest in the civic potential that could arise if gaming was re-developed and it is the people with most power, governments and military forces, who are recognising this potential and how to harness it. Rather than the social services of our most at need, including in schools and education settings (Kahne et al, 2009; Shafer et al, 2005; Salen, 2007; Engerman et al, 2017). From this review a hypothesis emerged that young people are at risk of addiction and future manipulation within these systems.

Further to this, the epigenetic consequences on the developing brain for addiction to gaming needs to be studied more. A parallel exists within the literature of epigenetic consequences of substance use addiction and disorders (Cadet & Jayanthi, 2021) and that of similar gaming addiction behaviours and psychological processes (Kuss & Grifiths, 2012). Recent research has identified that the addictive nature of substance misuse can cause changes in the epigenome, specifically modifying reward circuitry (Shepherd & Nugent, 2023). Within our investigation it is clear from the participants voice, and theme development, that there is an identification with behavioural patterns of addiction. What consequences will this have on the human epigenome? Specifically, humans identifying as male that are the main users of online gaming in addictive quantities.

The literature search also brought up the interesting question of what to do with technology, like the gaming industry, that has great power, following and hold. When used for good there appears to be evidence that it could shift education productivity, engagement and enjoyment for the masses, but currently as Gee (2003) states “gaming is a capitalistic driven Darwinian process of selection of the fittest” (abstract). That appears to use Draconian systems and processes that appeal to the normalisation of violence that we are seeing increase throughout our societies (Prescott et al, 2018; Krzyzanowski, 2020). Interestingly, one meta-analysis looking at the relationship between violent video games and violent behaviours noticed the effect was largest in White ethnicity groupings. Putting forward some evidence that ethnicity alongside sex may be a modifier of this relationship (Prescott et al, 2018).

The literature search produced enough material to make future suggestions of a meta-analysis in this area. But due to the restrictions of this unit and the specific qualitative papers provided for this investigation we continue here with the meta-synthesis to attempt to find a new understanding from the data we have, examining the meanings and experiences presented and adding a contribution to the field.

Research question:

From the literature review identifying the wider implications of gaming for young people’s development across their lifespan the following research question arose:

How do young people view their relationship with online gaming and its addictive nature?

Method:

This paper attempts to address the need to aggregate current data systematically in the field of online gaming addiction by using the methodology of a meta-synthesis to capture and interpret existing data in four published papers. To organise and recognise themes using the method of thematic analysis, which allowed for a detailed exploration of patterns.

As a result of the literature review, and the premise that there is an existing issue with online gaming addiction, a deductive approach to the thematic analysis occurred looking for codes to support either the enquiry towards structures that may reduce or diminish the addictive nature of gaming. Or in fact discover codes that identify the processes towards interventions that could become protective in nature for young people at risk of addictive gaming. These ideas became the framework to move forward with coding the data. As coding continued a recognition of novel themes emerged and that the existence of an inductive approach was also present, one that allowed space for the creation of new knowledge (Willig, 2022).

A mixture of data driven semantic codes appeared in the initial coding, but as the transcripts were reviewed in additional analysis, and conversations within the team of coders, latent codes also appeared. This allowed for the surface and underlying meanings to be captured (Braun & Clark, 2013)

Sample: Four published papers were provided by the University of Wolverhampton for the meta-synthesis, these can be found in appendices 1 to 4, alongside their coding and themes encapsulated within comments. The papers were published between 2013 and 2021 providing a selection from the last 10 years. The four papers came from the international community and were not based in the same area for collection of data, allowing for a good sample of research participants. Research participants in all 4 of the papers were young people, under the age of 18, who appear to be the focus and often main casualty of online gaming. In 3 of the paper’s participants were in education settings. One paper focused on individuals that were in treatment for their addiction to online gaming. It would be advantageous for future studies to include a wider age range and look at the impact of gaming via a longitudinal study into adulthood and beyond.

Method of coding: The method of coding used for all four papers was a broad and complete coding aiming to discover all that was available rather than a specific data set (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Using organic familiarisation with the transcript recorded on Word with no assisted software. The four papers were coded by a team of researchers from the university who were able to meet on a variety of occasions to discuss coding, before common themes across all papers were analysed by authors individually. The findings and results section from each paper became the transcript that was inserted as data in one column of a Word document and in another column the search for codes began, via reading and familiarisation of the transcript. The author of this paper coded two papers, paper 1 (appendix 1) and paper 2 (appendix 2) and received two papers that had been coded by another group member (appendix 3 and 4). This allows for a broad double coded analysis of data, which should increase the reliability of findings (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020).

Results:

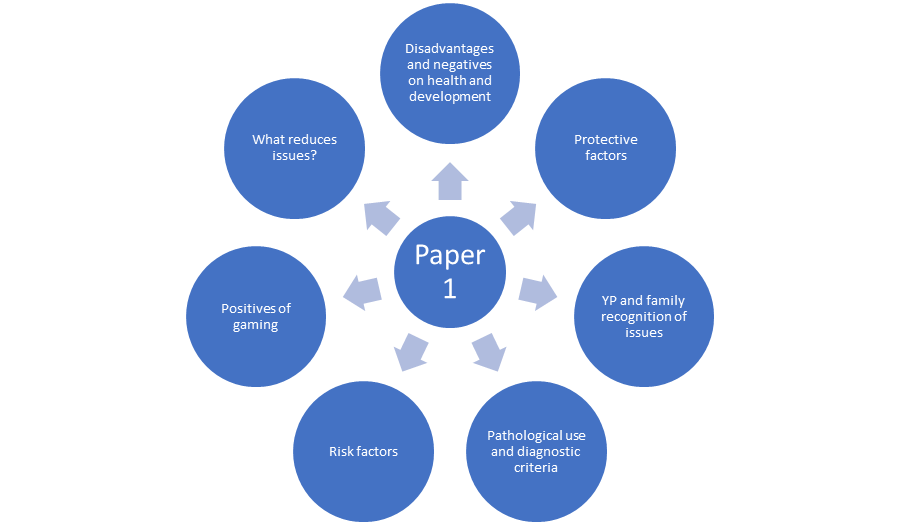

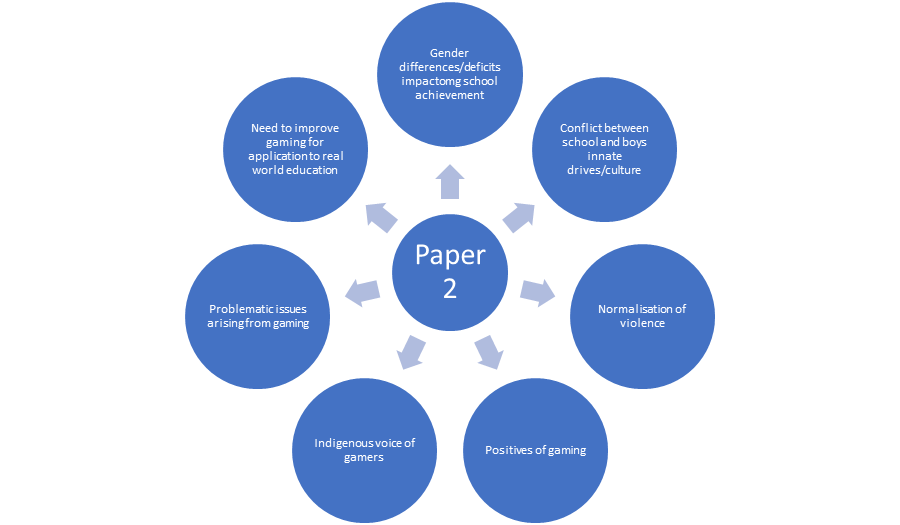

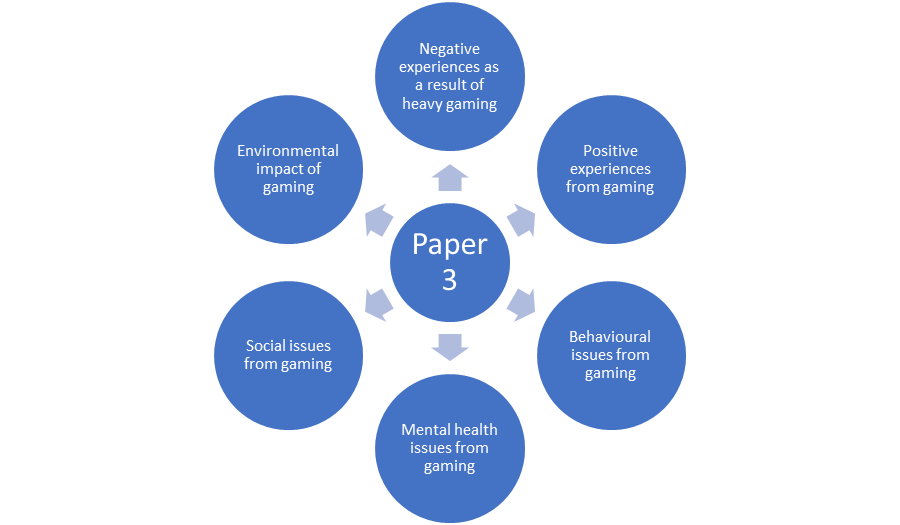

Development of Sub Themes within each paper.

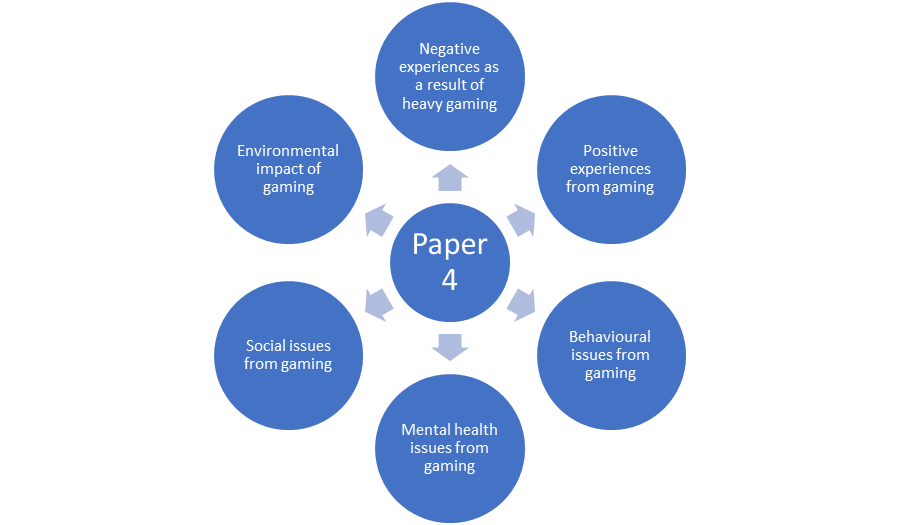

Diagram A.

Diagram B.

Diagram C.

Diagram D.

Development of Themes.

Table 1.

| Theme Name | How many times mentioned |

| Advantages of online gaming Acquisition of historical information Development of critical reading skills Development of meaning making Language development Development of strategy Teamwork and collaboration Literacy skill development Gaming can support education and learning Transferability of embodied actions and skills Learning opportunities Enjoyment of learning transition to classroom Motivation Communication skills Leadership skills Communication skills Disadvantages of online gaming Confusion and distortions of reality Addictive nature of gaming Dangerous identification with characters Violent interactions within gaming Playing too long/often creates issues Problematic relationships Neglecting the real word Mental health concerns – mood disturbance – variety of disturbances Social isolation Bullying and aggressive behaviours towards others Effects of video games on physical health Recognition of negative impact on life for young people Protective factors for addictive gaming Access to screens and time management Indigenous voices Autonomy of access Development of boy culture for real world application Positive parental engagement creates protective factors Variety of family structure Positive parental engagement high protective factor Choosing less addictive games – regulation of play Risk Factors for addictive gaming Deleterious family and social environment Alienation from traditional learning Immersion and feelings of belonging – escapism Feelings of hopelessness and isolation Social status and relationships – competition increases usage Significant playing time, neglecting real world, confusion of worlds Mental health issues possible risk factors Congruent definition of pathological game use with DSMV | 120 14 11 8 5 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 70 7 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 2 2 3 58 8 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 29 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 |

Overview of results from analysis:

The initial subthemes as seen in diagrams A to D provided a fascinating overview and richness of the research and allowed themes to develop across all four papers.

It is evident that there are some positive uses for online gaming (see table 1), that the potential for educational content is a real driver for change in the current environment. This is one of the main subthemes and we can hear researchers draw on this often. “Game[s] required such a large amount of reading that our respondents reported developing advanced vocabulary for their respective ages”. Participants self-identified with this also, “I probably learned a lot of vocabulary from those games… believe it or not. Just cause it was constantly reading, reading, reading”. Educators “could use these immersive and engaging environments to separate fact from fiction elevating interest and driving critical analysis of content within reliable resources”.

Specifically, the application and acquisition of historical data, this appears to be one of the main areas of positive interest for gamers particularly within paper 2 (appendix 2). This “may demonstrate that games have the potential to provide domain specific content along with transferrable learning opportunities”. An experience that is currently submerged in the gaming environment and one that could be improved on without gamer disconnection. As is evident in this participants synopsis:

“Greg indicated, Probably, in social studies this year. We were talking about the war…. and I knew everything. … Yeah and I knew, Revolutionary War. I just really knew everything, and I know this other kid who played it, and he’s in my class and me and him just like (chuckles)… yeah, we knew everything. (Greg) Greg described the embodied experiences within the game and was proud of his ability to recount events for his classroom audience.—‘‘yeah, we knew everything’’. Greg’s excitement and confidence here also illustrated his attempt to make a connection between school literacies and his own life literacy practice”

One of the issues currently however is the lack of accurate historical data within online gaming: “Although limited in factual data, respondents described experiences such as these as being highly meaningful to them”. The lack of accurate factual data and the risk factors for addictive behaviours, such as being alienated from mainstream education or those who come from “deleterious family and social environment” that may not scaffold the young person’s learning in anyway, are all disadvantages and risks of online gaming and pull the area subconsciously at times into chaos. There is a huge opportunity here to change the way that young people are educated and held in their innate learning spaces but these risk factors and more would need to be addressed.

Outline of key themes that emerged:

The key themes that emerged where the signifcant advantages and disadvantages of gaming for young people. Alongside this the risk for these young people to engage in addictive gaming and what protective factors were available to them. These became the central and organising concepts (Braun & Clark, 2013) of the research and gave grounds to make the following suggestions.

Advantages – online gaming has a large potential to educate young people (Salen, 2007; Apperley & Walsh, 2012), particularly for young people at risk of exclusion from mainstream education (if the material becomes factual appropriate). The young people “described being motivated to communicate through speaking and listening as they socially played with peers, which improved their speaking and listening skills towards collective objective”. The data showed that there were many possibilities for education:

“The boys described the ability to acquire and [use] accurately a range of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases sufficient for reading, writing, speaking, and listening at the college and career readiness level; demonstrate independence in gathering vocabulary knowledge when encountering an unknown term important to comprehension or expression”.

Most importantly that through listening to what motivates young people, their indigenous voices, about what encourages learning opportunities and how this could be harnessed through gaming “this illustrates the power of interest driven learning” and what the future of gaming could be.

Disadvantages – online gaming if done at high frequency, for specific populations of people can become a negative space in which addictive behaviours are paramount to any other. The data collected evidenced the following issues arising from online gaming:

“Affective problems, verbal problems, self-control problems, and behavioural problems. Focus group interviews indicate peers to suffer from heavy gamers’ bullying and physical assaults, claiming they do not obey classroom rules and neglect their educational and social responsibilities. Verbal problems include acts such as teasing and making fun of other individuals, using nicknames, and swearing”

That heavy gamer “conversation is always somehow connected to video games, and this is boring” this detail came up regularly and demonstrates the impact on social and intimate relationships. This point also impacts the possibility of young people becoming isolated from peers and loosing themselves in gaming and away from reality, significantly “reported by gamers from their playing experiences is the escapism and/ or dissociation that gaming allows”.

Participants mentioned: “The fact that you can change your life. For what you are in the game”, ““I find myself dreaming about the game characters and scenes”, “escape other conflicts in their lives”, ““I thought it relaxed me but stressed me much because of the pressure my parents exerted on me. I played to forget almost everything”, “my mind disconnected”, “I lose control. I don´t know how much time has passed”. These are common statement across the four papers and demonstrate that users are often playing for escapism reasons. Alongside “the danger residing in the identification with ‘bad characters’ and the risk of committing regrettable acts (violence, substance dependence)”.

There were so many disadvantages and here are just a few examples: “I started to get depressed and play more”, “poor academic performance”, “, not looking for a job, and/or working part-time to play in the afternoon”, “some cases lead to consequences such as forgetting to eat”. That it really showed the need to publicise and support users with more education around how to care for themselves whilst gaming and how to notice excess usage.

Risk factors – specific risk factors such as “deleterious home environments” and young people at risk of exclusion, social isolation and mental health concerns are a very real concern. There was a huge emphasis throughout all papers that:

“parental conflicts and indifference toward their children [became] to be the main reasons for this situation: I know these three students share a mutual misfortune and all of them have problematic experiences with their parents. Their mothers and fathers have no interest in them, which strikes me as why these children prefer playing video games, to avoid their parental problems”.

Other key risk factors in the main themes were “the type of game was blamed, especially war games”, the alienation of young people from traditional learning “an environment without friends or in an isolated location was compensated by a great investment in the virtual world”.

Alongside “three principal elements to describe this pathological use: ‘not knowing how to stop gaming’, ‘not meeting your obligations’, and ‘doing nothing but gaming’”.

The risk of engaging in heavy usage was very present in young people who had feelings of hopelessness and isolation:

“Gamers with pathological playing habits confused the real and virtual worlds. Therefore, they could transpose actions from the virtual into the real world, risking violent acts or sexually dysfunctional behaviours. This confusion was enhanced by isolation, the gamer having a poor understanding of the real world. The realistic nature of a game also facilitated this confusion”.

Although not a main theme within these papers “the omnipresence of video games in contemporary society (advertising, special events) was thought to encourage gaming”, which fits with the wider literature review of penetration from a Capitalistic market (Gee, 2003).

Protective factors – the young people who engaged in these studies had a very clear voice around what may help to protect against addictive gaming, factors such as limited screen time “the adolescents agreed on the need to regulate their habit” also that “adopting systems to manage the amount of time spent gaming reduced the risk of pathological use”. The types of games played and reducing violent games also “complying with PEGI (Pan European Game Information) could avoid problematic use”, specifically age-appropriate games. Most of all autonomy over their own usage with significant family (parental positive input) “the main protective factor referred to was parental control, which should be seen as a support mechanism that changes with the maturity of the adolescent and enables the adolescent to attain self-control based on dialogue and trust”.

Our data demonstrated that seeking support from professional resources or loved ones can also be beneficial in overcoming addiction and promoting positive behaviour change, in statements such as: “family physicians are encouraged to take a ‘media history’ from patients and discuss connections between a child’s health and behaviour and screen use”. This kind of intervention needs to become more commonplace when supporting young people with gaming.

Discussion and Implications for future research

Interestingly one of the most powerful themes that arose from the thematic analysis was that of the indigenous voice of young people using online gaming. That they as individuals recognise the risk factors for gaming becoming addictive and problematic and could identify themselves what would be protective in nature. Thematic analysis is particularly adept at identifying research questions that consider individuals conceptualisation of specific social phenomena (Willig, 2021). For this research that has been prominent throughout and leads to the suggestion that guidance and regulations within the industry need to consult users as a priority matter. Also, that as escapism from problematic lives was a high indicator for heavy usage that this needs to be addressed in protective interventions to reduce addiction.

Young people who use online gaming can have a spectrum of associated behaviours and cognitions, from unproblematic to addictive. Their view of this relationship is insightful and accurate. As their lifelines unfold these young people’s environments influence their gene expression (Roses, 2005), what limits and potentials does this create? Future research needs to look to epigenetics to better understand the complex processes that can lead to addiction. As with other areas of mental health the lived experiences of people in distress have become imperative for recovery and change.

With the growing evidence of the impact of addictive behaviours on the epigenome (Cadet & Jayanthi, 2021) and the increasing usage of online gaming – with global online gaming revenues of £23.56bn USD in 2022 (Clement, 2022) we propose that an urgent safety review for young people and their heavy usage be undertaken. So that we can safeguard their development and utilize online gaming for better more educative purposes.

Reflexivity section

In undertaking this analysis of data, I had many pre-existing thought processes arise. Some Feminist in their criticism of the toxic online spaces that are present for females and that there appears to be a normalisation of violence in these spaces (O’Halloran, 2017).

Also, noticing male peers in my world who use online gaming for escape from problematic and difficult lives. The ability to be able to submerge yourself in a game can provide relief and a strategy to cope with complex issues. However, this does not tackle the issues and draws the individual away from the connection with reality that they really require to move forward and through issues.

My subjectivity of this area was important to be aware of during the coding process and notice specific codes such as ‘normalisation of violence’ and to ground my experience in the data. I also felt it was important to recognise the heuristic nature of my enquiry from personal experience in this area. I took a social constructionist approach to this analysis of data but felt aware throughout that this approach does not adequately consider ‘power’ (Nightingale, 2011) which I feel is a pervasive part of the periphery of this conversation.

References:

Apperley, T., & Walsh, C. (2012). What Digital Games and literacy have in common: A heuristic for Understanding Pupils’ Gaming Literacy. Literacy, 46(3), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4369.2012.00668.x

Beranuy, M., Carbonell, X., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). A qualitative analysis of online gaming addicts in treatment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 11(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-012-9405-2

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. Sage Publications Ltd.

Cadet, J. L., & Jayanthi, S. (2021). Epigenetics of addiction. Neurochemistry International, 147, 105069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105069

Chen, S., Wang, M., Dong, H., Wang, L., Jiang, Y., Hou, X., Zhuang, Q., & Dong, G.-H. (2021). Internet gaming disorder impacts gray matter structural covariance organization in the default mode network. Journal of Affective Disorders, 288, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.077

Cisamolo, I., Michel, M., Rabouille, M., Dupouy, J., & Escourrou, E. (2020). Perceptions of adolescents concerning pathological video games use: A qualitative study. La Presse Médicale Open, 2, 100012. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-32271/v1

Clement, J. (2022). Topic: Online gaming. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/1551/online-gaming/

Engerman, J. A., MacAllan, M., & Carr-Chellman, A. A. (2017). Games for boys: A qualitative study of experiences with commercial off the shelf gaming. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(2), 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-017-9548-8

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment, 1(1), 20–20. https://doi.org/10.1145/950566.950595

Kahne, J., Middaugh, E., & Evans, C. (2009). The Civic Potential of Video Games. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Krzyżanowski, M. (2020). Normalization and the discursive construction of “new” norms and “new” normality: Discourse in the paradoxes of populism and neoliberalism. Social Semiotics, 30(4), 431–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2020.1766193

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Internet and gaming addiction: A systematic literature review of neuroimaging studies. Brain Sciences, 2(3), 347–374. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2030347

Nightingale, D. J. (2011). Social Constructionist psychology: A critical analysis of theory and Practice. Open Univ. Press.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940691989922. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

O’Halloran, K. (2017, October 23). “hey dude, do this”: The last resort for female gamers escaping online abuse. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2017/oct/24/hey-dude-do-this-the-last-resort-for-female-gamers-escaping-online-abuse

Prescott, A. T., Sargent, J. D., & Hull, J. G. (2018). Meta-analysis of the relationship between violent video game play and physical aggression over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(40), 9882–9888. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611617114

Roses, S. P. (2005). Lifelines: Life beyond the gene. Vintage.

Salen, K. (2007). Gaming literacies: A game design study in action. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 16(3), 301-322. Waynesville, NC USA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved April 16, 2023 from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/24374/.

Shaffer, D. W., Squire, K. R., Halverson, R., & Gee, J. P. (2005). Video games and the future of learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 87(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170508700205

Shepard, R. D., & Nugent, F. S. (2023). Epigenetics of drug addiction. Handbook of Epigenetics, 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-91909-8.00040-2

Willig, C. (2022). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. Open University Press.

Yılmaz, E., Yel, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). The impact of heavy (excessive) video gaming students on peers and teachers in the school environment: A qualitative study. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.15805/addicta.2018.5.2.0035